Columbus : The earth is not flat, Father, it’s round!

Columbus : The earth is not flat, Father, it’s round! The Prior : Don’t say that!

Columbus : Its the truth; it’s not a mill pond strewn with islands, it’s a sphere

The Prior : Don’t, don’t say that; it’s blasphemy

Dialogue from 'Christopher Columbus', A Play by Joseph Chiari

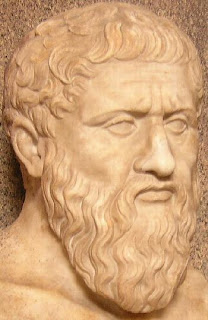

In a momentous passage from book 2 of ‘On the Heavens’, Aristotle concludes that the earth is spherical:

Either then the earth is spherical or it is at least naturally spherical. And it is right to call anything that which nature intends it to be, and which belongs to it, rather than that which it is by constraint and contrary to nature. The evidence of the senses further corroborates this. How else would eclipses of the moon show segments shaped as we see them? As it is, the shapes which the moon itself each month shows are of every kind straight, gibbous, and concave-but in eclipses the outline is always curved: and, since it is the interposition of the earth that makes the eclipse, the form of this line will be caused by the form of the earth's surface, which is therefore spherical.

Again, our observations of the stars make it evident, not only that the earth is circular, but also that it is a circle of no great size. For quite a small change of position to south or north causes a manifest alteration of the horizon. There is much change, I mean, in the stars which are overhead, and the stars seen are different, as one moves northward or southward. Indeed there are some stars seen in Egypt and in the neighbourhood of Cyprus which are not seen in the northerly regions; and stars, which in the north are never beyond the range of observation, in those regions rise and set.

All of which goes to show not only that the earth is circular in shape, but also that it is a sphere of no great size: for otherwise the effect of so slight a change of place would not be quickly apparent. Hence one should not be too sure of the incredibility of the view of those who conceive that there is continuity between the parts about the pillars of Hercules and the parts about India, and that in this way the ocean is one. As further evidence in favour of this they quote the case of elephants, a species occurring in each of these extreme regions, suggesting that the common characteristic of these extremes is explained by their continuity. Also, those mathematicians who try to calculate the size of the earth's circumference arrive at the figure 400,000 stades. This indicates not only that the earth's mass is spherical in shape, but also that as compared with the stars it is not of great size.

In God and reason in the Middle Ages, Edward Grant writes that:

In God and reason in the Middle Ages, Edward Grant writes that:‘All medieval students who attended a university knew this. In fact any educated person in the Middle Ages knew the earth was spherical, or of a round shape. Medieval commentators on Aristotle’s 'On the Heavens' or in the commentaries on a popular thirteenth century work titled ‘Treatise on the Sphere' by John of Sacrobosco, usually included a question in which they enquired ‘whether the whole earth is spherical’. Scholastics answered this question unanimously: The earth is spherical or round. No university trained author ever thought it was flat’

John of Sacrobosco's book, the ‘Treatise on the Sphere' or 'Tractatus de Sphaera' mentioned by Grant, was published in 1230. This popular work discussed the spherical earth and its place in the universe and was required reading by students in all Western European universities for the next four centuries. If the 'poor benighted medievals' had really believed that the earth was flat as was claimed in the 19th century, they must have been ignoring their own textbooks. Perhaps the heavily annotated copy of 'Treatise on the Sphere' shown on the right has been graffitied by scholasitics claiming 'it's not true!' and 'this is heresy!'; but I highly doubt it.

And yet the popular conception of Columbus’s voyage is that he discovered the world is round, in the process refuting the medieval view. The culprit here was Washington Irving, which conjured an imaginary scene in which Columbus pleads his case for a spherical earth in front of Church dignitaries and professors in Salamanca. In Washington’s imagination, Columbus ‘who was a devoutly religious man’ was assailed ‘with quotes for the Bible and the Testament...such are the specimens of the errors and prejudices, the mingled ignorance and erudition and the pedantic bigotry with which Columbus had to contend’

The truth is that when Columbus was planning his voyage, he gathered evidential support from a scholastic treatise entitled ‘The Image (or representation) of the world (ymango mundi)’ which had been written by the theologian and philosopher Pierre d’ Ailly and was one of the most popular printed books in the later fifteenth , sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Not only did D’Ailly say from the very outset of the treatise that the earth is a sphere, but he also cited Aristotle and Averroes in reporting that the end of the habitable earth towards the east and the end of the habitable earth towards the west are very close with a small sea in between. D’ Ailly reported the earth’s circumference as 56 2/3 miles multiplied by 360 degrees, as measured by Alfraganus (al-Farghani). Edward Grant reports that, in Columbus’s annotated copy of the book, this circumference measurement has been written in the margin and surrounded by boxes to emphasise the point. This was important for Columbus because it made the world seem much smaller than it actually was, so that sailing from Spain to India would require only a few days to cross the small sea. In fact, by going with the smaller estimate Columbus had underestimated the distance he would have to travel to India, and had the Americas not been in his path he would have run out of provisions.

Not only did Columbus not discover that the earth was round – that had been the scholarly consensus since Aristotle, despite the best efforts of the self educated Cosmas Indicopleustes – he gained the information for his voyage from medieval sources.

Not only did Columbus not discover that the earth was round – that had been the scholarly consensus since Aristotle, despite the best efforts of the self educated Cosmas Indicopleustes – he gained the information for his voyage from medieval sources.As Grant concludes in ‘God and reason’:

Although some progress has been made in rectifying the egregious historical error that a flat earth was commonly assumed in the Middle Ages, the error lives on. Perhaps it is because, as Russell plausibly suggests ‘the idea of the dark middle ages is still fixed in the popular consciousnesses and consequently ‘no caricature is too preposterous to be accepted.

Discuss this post at the Quodlibeta Forum